For many Iranians, the contemporary history of the country is divided into before and after September 16, 2022, the day Mahsa Amini, a 22-year-old young woman, was killed in the custody of the morality police (for not having what was called the proper hijab). In response to this incident, people all over the country came to the streets to protest against the regime that has used the mandatory hijab law as an excuse to suppress women for more than forty years since the 1979 Islamic Revolution. The scope of these protests went far beyond what was imagined and continued for more than six months. Unsurprisingly, such large-scale protests spread to Iranian theatres, especially since the very first days, many theatre practitioners were jailed for participating.

In an early reaction, published as a signed statement on social media, protesting practitioners announced that they would no longer participate in the “production and spectatorship” of works where women must wear the mandatory hijab. Following this, there was a severe and widespread discussion about the “theatre ban” among practitioners. Those in favor of the ban stopped working in official theatre spaces or watching state-sanctioned plays that were staged under supervision and in compliance with dictated criteria. In their view, the actions happening on the streets (from rallies to women’s resistance to wearing the compulsory hijab in public despite all the dangers) are much more progressive than the censored and passive performances in official theatres where they have to hide their words in “metaphors” and allegories.

On the other hand, the artists who opposed the ban on theatre and the halt of artistic activities by theatre groups saw this as a form of self-imposed exile. They argued that emptying the stages of practitioners and closing the theatre is precisely what the state has been seeking for. However, proponents of the official theatre ban argued that alternative spaces can act as a solution to keep the art alive and turn the performances into protest actions.

Utilizing alternative spaces has been a familiar tactic of Iranian artists (in all disciplines) in response to restrictive supervision imposed on them as a result of the regulations set during the Cultural Revolution (1980-1983). However, a significant difference is evident. Previously, underground performances were confined to private spaces like apartments and private parking lots, with limited accessibility to only a few people. Now, they are frequently organized in more public settings, such as non-governmental cultural centers that endorse this movement, enabling a much larger audience to participate. Knowing these facts, when I traveled to Tehran in June 2024 to participate in some of these performances, I was still unsure what changes I would experience in the atmosphere of Iranian theatre after being away for two years.

The first question that came to my mind was: where are these performances taking place, and how can I get tickets? I soon realized that theatre groups use social media to share information about their performances. However, in the posts and stories shared by people affiliated with the group, there is often no mention of the location or time of the performance or any details about the performers. Instead, they would only introduce one person (a connection) tagged in that post or story. Then, after introducing themselves to the connection and buying tickets, the audience will be informed of the time and place of the performances.

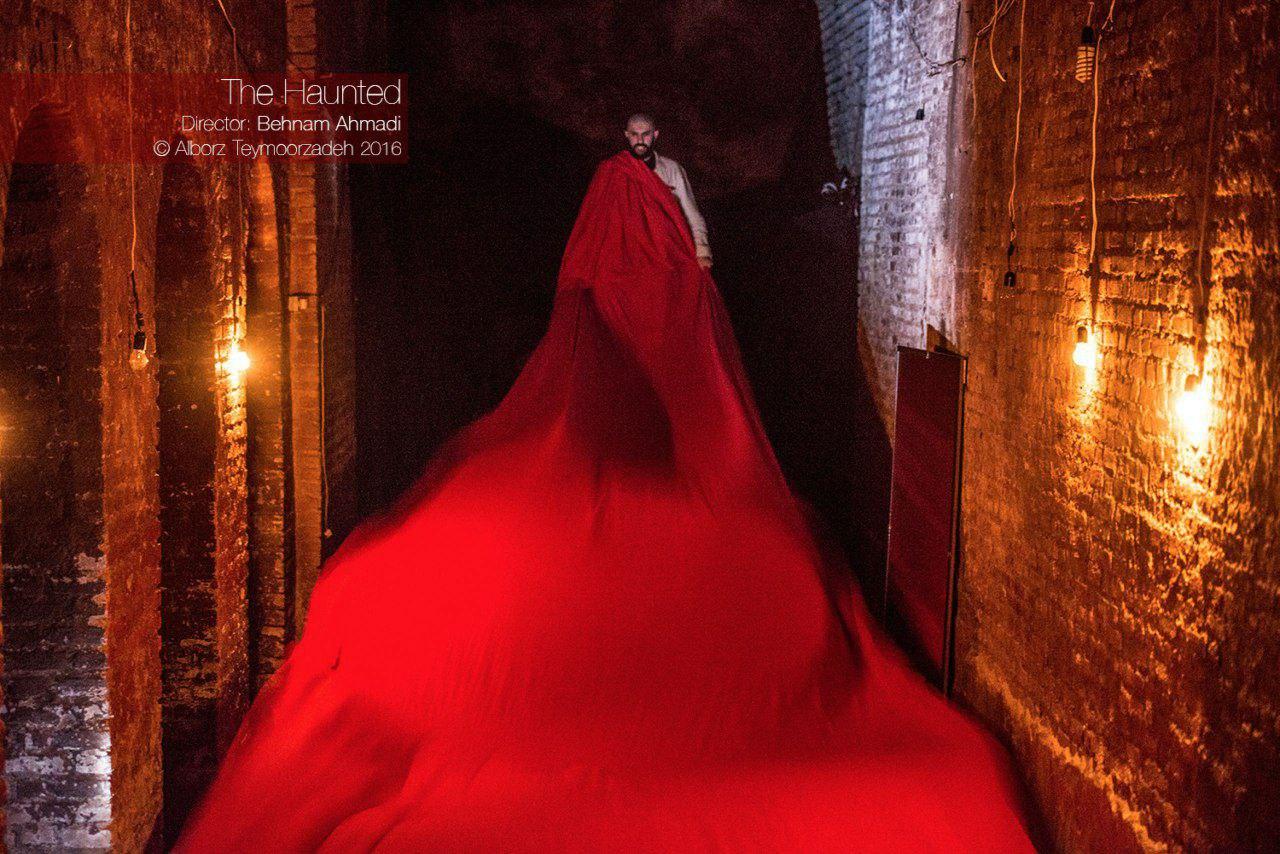

The strange and paradoxical fact is that, unlike in the past, many of these shows are not performed in private spaces but in cultural centers that have received official permission from the state’s Ministry of Culture for their activities. Therefore, these centers, while officially licensed for their activities, have ironically become the primary locations for unlicensed performances through their licensed activities. Most of these cultural centers are situated in aged structures within the heart of Tehran, which formerly served as residential dwellings before their conversion. Usually, these centers have designated spaces for theatrical performances, which can be located in various places such as rooms, basements, or yards, depending on the building’s architecture.

In the absence of proper lighting, sound, or other facilities in these spaces, many theatre groups try to have site-specific performances by tailoring their ideas to the spaces to which they have access. In one of the performances held in a basement, at the show’s beginning, the female performer/dancer was seated on a chair on a concrete platform that was part of the room. Due to the basement’s low ceiling, the performer was practically trapped in a bent and very uncomfortable position. This spatial limitation and the struggle to free from it had become the main idea of this performance. Then, when the performer could pull herself up and get down from the chair, she freely explored and familiarized herself with the entire basement space. In the end, when she noticed a hatch in the ceiling, she pulled herself up from it and left the basement.

Some groups have used the “theatre ban” and withdrawal from state-sponsored events as themes in their performances. In one of the most impressive shows I saw, the performers—all the actual directors who had withdrawn from participating in the state-sponsored Fadjr Theatre Festival in protest —were acting as festival judges, reporting the details of shows that were never performed. The judges explained that among the artists who had withdrawn from performing in this festival, a young woman named Ayna (Ghotbi Yaghoubi) was supposed to perform a play called We Burned, You Burned, They Burned. After explaining Ayna’s idea for her show in detail, they noted that she passed away from cancer before she had another opportunity to perform her show. Then, the performers, in the role of judges of a festival that was never held, presented the prize for that edition of the festival to Ayna.

Underground theatre artists do not adhere to the government’s dress codes and freely address topics that are censored on official stages due to constant surveillance and censorship. For years, artists had to find ways to indirectly or discreetly portray intimate relationships and sexual issues or avoid them altogether. Now, in the more liberated environment of underground theatre, some are bravely addressing sex openly and directly. The performers do not feel the necessity to appeal to euphemism while discussing sexual matters, and, although it is not common, sometimes they even go so far as to risk experiencing some degrees of nudity and intimacy in front of the audience.

In one of the performances, which seemed like a collage of the different characters’ lives gathered together at a party, we got access to the most private moments of their lives. At the beginning, the audience entered the dance scene of a party where men and women danced passionately with each other. Contrary to the expected standards of the official Iranian theatre, they danced together in close contact. This extended scene continued until the abusive behavior of a male actor bothered her female dance partner. The young woman, who initially seemed happy dancing with him, gradually grew more and more uncomfortable until she suddenly started slapping her abusive companion, which brought the party to a halt. After that, in separate episodes, we learned the inner fears of those present at the party. In one episode, a partially unclothed female performer expressed her concerns about her body while getting dressed for the party.

Performing without government permits has allowed Iranian artists to participate in activities and gain experiences that were previously impossible, even if they may seem trivial and simple. In a conversation I had with an actress friend of mine, she told me that the first time she performed on stage without the mandatory hijab, she felt as if a new organ had been added to her body, which she still could not control well on stage. Despite that, she believed her hair would give her new acting capabilities.

The underground setting has also enabled artists to explore the dynamics of close interaction between male and female actors and the possibility of physical contact on the stage, which the state has strictly forbidden for more than four decades. In one of the shows, two actors, a woman and a man, played the roles of a couple. The woman’s character had died in a car crash, and the man, who was a writer, felt guilty because he had imagined her death in one of his stories and now blamed himself for her tragic ending. The actors combined everyday movements with dance and freely touched and held each other’s hands. Their close interaction allowed for delicate movements, conveying the characters’ lost intimate relationship, which could easily be lost with a lack of physical contact.

It is because of these freedoms in choosing the topics and the way of expressing them that many performers and, of course, spectators, despite all the risks, prefer attending small underground spaces to professional venues. However, as they expand and gain more attention, there is always a risk that state regulators will take a more stringent stance to suppress and deter underground experiences. With the establishment of a semi-reformist government in July 2024 and the relative moderation of the cultural atmosphere, some artists who have not been active since September 2022 are expected to once again return to the official theatre stages. However, it seems unlikely that all of this will have an impact on the growth of the burgeoning underground trend, which has provided a new direction for Iranian theatre artists.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.