After a 2008 run at the Luminato Festival netted it a Dora Award for best new opera, Tapestry Opera’s family-friendly Sanctuary Song has returned in a slightly expanded version to conjure a vision of our man-made world through the eyes of a remarkable, resilient elephant.

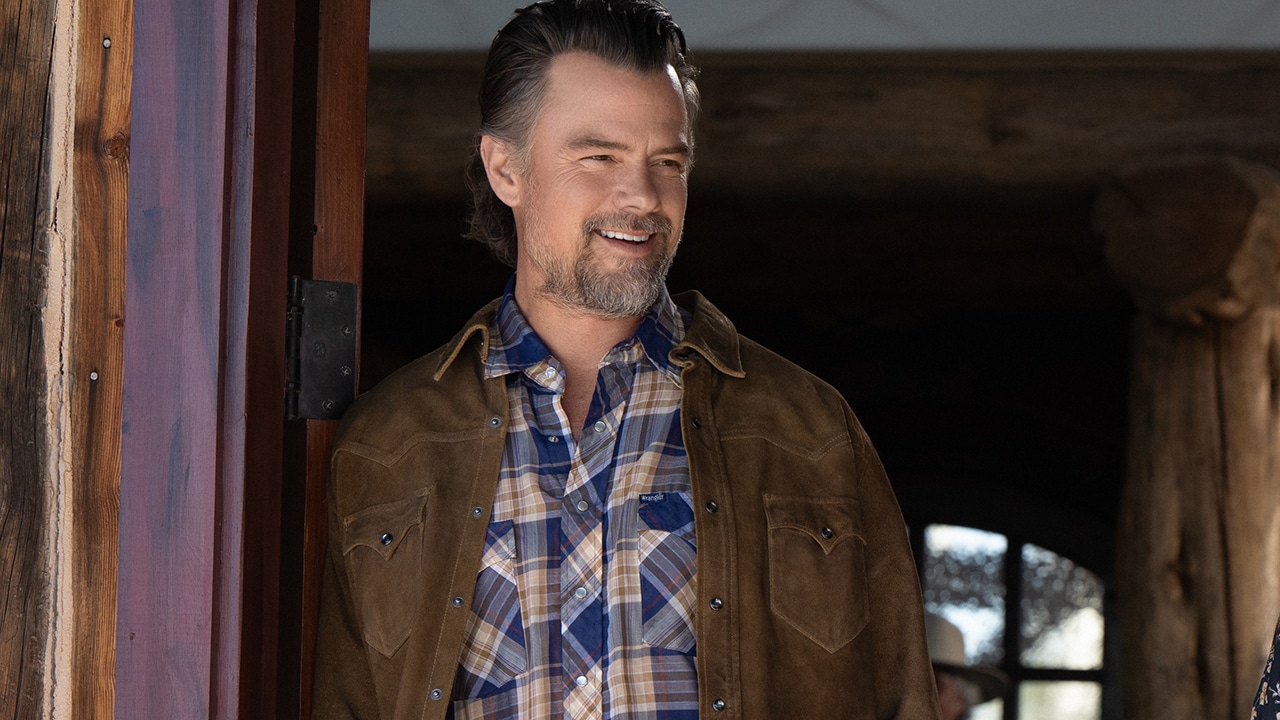

In the show’s preamble, the theatre performer Courtenay Stevens enters the Nancy and Ed Jackman Performance Centre on stilts and makes partially improvised banter with the audience.

“Who puts on an opera in a basement on Yonge Street?” he asked at one point, and a few people lightly chuckled — including, I noticed, Tapestry Opera’s artistic director Michael Hidetoshi Mori. In his remarks after the opening night performance, Mori explained what he likes about the newly launched venue’s subterranean location just north of the Toronto Reference Library, which it shares with St. Clare’s Housing and Nightwood Theatre; he said it reminds him of bars and cafés in New York with entrances that are unassuming but full of possibility. This sentiment falls in line with his ethos as a creator, as stated at the end of his 2015 TEDx talk on labelling opera: “Without definitions, [and] with a little bit of curiosity, the world becomes more interesting and more exciting.”

After Stevens continues with his act — which involves falling down, missing his lighting cues, and pulling the wool over the eyes of an audience participant — the opera begins in earnest.

On a curved ramp, behind which flutters a fringe curtain that serves as a projection screen for Wangyang-inspired shadow puppets, Louisiana zookeeper James (the impeccable baritone Alvin Crawford) attempts to lead a resistant elephant named Sydney (a grand and graceful Midori Marsh) onto a truck heading to a sanctuary in Tennessee. (In The Urban Elephant, the PBS documentary that inspired the opera, James bathed “Shirley” to calm her down before utilizing a winch to ease her in; in Sanctuary Song, he merely reminds her: “You need more than what I can give.”)

As the codependent pair ride in the truck, their anticipated separation triggers a series of reminiscences, with Marjorie Chan 陳以珏’s libretto flashing between past and present. Sydney and James must grapple with this remembered sequence of chaotic events — involving gunshots, boat fires, black chains, and heavy leather whips — before a fugitive sense of hope for the future can alight for the two of them.

To portray the elephant characters in an elegant, unobtrusive manner, set and costume designer Jung-Hye Kim has fashioned hats with flattened sleeves for ears, sashes to represent their liberated states, and cuffs that allow arms to transform into trunks. With the fringe curtain, Kim has tactfully innovated a solution to entrances and exits within this wide yet shallow space — which, depending on where you’re seated, partially obscures the orchestra on the left, the surtitles on the right, or the circus ring downstage.

“I remember,” Sydney often exclaims, and whenever she does, pianist Talisa Blackman, violinist Aysel Taghi-Zada, and percussionist Ryan Scott work in tandem to bring Abigail Richardson-Schulte’s most affecting compositions of the evening to life — rippling musical interludes that mirror the power of Sydney’s memory, of how it acts as a refuge for this refugee.

The show succeeds in juxtaposing contrasting emotions — the pleasures and the pains of friendship. It captures how one can go from feeling full to empty in a split second: in a flashback, where Sydney is sold to a Louisiana zoo after a leg injury, for instance, Bonnie Beecher’s circus-like lighting strips back and one can suddenly, viscerally feel Sydney’s social deprivation.

One of the less effective aspects of Sanctuary Song, which runs an hour long, is that Chan renders voiceless Sydney’s elephant friend Penny (an energetic Elvina Raharja) — rather than singing, she performs in saccharine dance sequences choreographed by Aria Evans. Thus Penny’s abrupt absence doesn’t have the impact it would’ve should she have been developed, as per Mori’s ethos, with little bit of (operatic) curiosity into her interiority.

The alienation of displacement, the isolation of captivity, the desire for liberation, the spectacle and shame of indoctrination: these are the psychological realities that opera, as a form, dramatizes best. But Sanctuary Song, which possesses all the potential to be an opera as singular as its subject, rushes through these themes like forgone conclusions instead of pacing itself with enough intention to earn the catharsis the source material is able to provide in the same amount of time. As a result of these mismanaged emphases, James’ final aria, “Alone,” feels tacked on when it — and Howard — should occupy the emotional core of the story.

“I don’t know who was the first to put a chain on her,” the real life James said the day he delivered Shirley to her sanctuary. “But I’m glad to know that I was the last to take it off. She’s free at last.” When a version of these lines make their appearance in Sanctuary Song, it gives a glimpse into the kind of political and narrative dimensions this opera — 17 years after its debut — could open up if its desire to be “appropriate for both children and adults” didn’t come at the cost of developing its characterizations and deepening its look at the moral relations between humans and animals (which wouldn’t necessarily exclude the child-like wonder it currently prioritizes showcasing).

Looking back on Sanctuary Song, what lingers in my mind is Marsh and Howard’s powerful performances; the jelly bean-shaped watermelon that Kim has thoughtfully included as a reference to Shirley’s favourite snack; and the idea that the downside of having an elephantine memory is needing to force yourself to forget all the parts you don’t wish to remember.

Sanctuary Song runs at the Nancy and Ed Jackman Performance Centre until May 25. Tickets are available here.

Intermission reviews are independent and unrelated to Intermission’s partnered content. Learn more about Intermission’s partnership model here.