Playing at the Scottish Storytelling Centre during the Edinburgh Fringe Festival, Cassandra, written and performed by Ailsa Dixon. This solo show, a compelling mix of music and spoken word, opens with Dixon playing both harp and cello – music that is powerfully interwoven into the narration. Her focus: the stories of women, past and present, human and mythical, who had a truth to tell, but their voices were supressed, or simply not listened to. Hence the title, Cassandra, a Trojan princess and daughter of King Priam and Queen Hecuba, who was blessed with the gift of prophecy by Apollo. We hear about how, when Cassandra rejected Apollo’s advances, he put a curse on her. Even if her prophecies were true, they would never be believed.

The play opens with this storyteller-musician presenting the story of a young woman in contemporary Edinburgh. One night, feeling frightened and troubled about the state of the world, she gets up and takes a walk. It is Dixon’s skilful use of detail and imagery that brings the woman to life. The woman is “dressed in a Gore-tex jacket and sensible shoes”, and as she walks higher and higher onto one of the hills, surrounding the city, “she can feel the wind blowing her cheekbones back”. She hears the voices of other women, too, who suggest other stories that come and go, just like the wind, a recurring element in the narration. Women from Scottish history and folklore, who suffered a similar fate to that of Cassandra, such as Mary Campbell loom large. In a flash, we are transported to early 17th century Scotland, where Mary hears voices and has premonitions when her baby dies stillborn. The church minister refuses to give the baby a proper burial since it hasn’t been baptised, so Mary buries it in her garden, along with an ash tree to commemorate its passing. Mary makes a prophesy that evil will befall anyone damaging the ash tree. She is not believed, even if years later, her prediction turns out to be true.

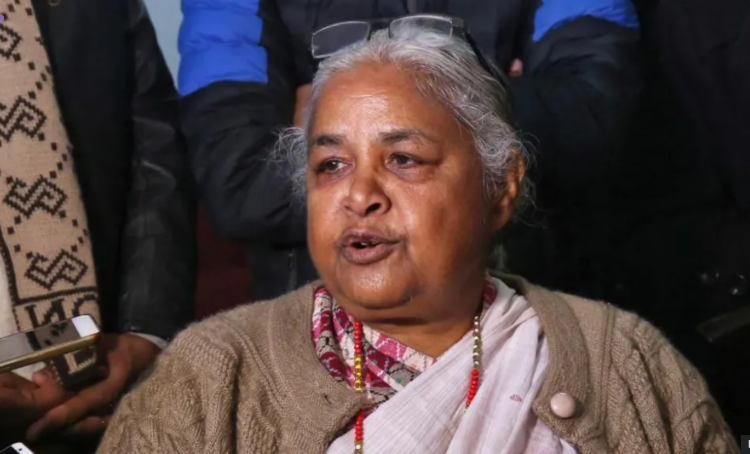

Cassandra, Edinburgh Fringe Festival 2025.

The narrator’s keen eye also travels to the faraway Orkney islands, a place where many women were accused of being witches in the 16th and 17th centuries. Janet Forsyth, known as the ‘Westray storm witch’, has the gift of prophesy and her story is even sadder than Campbell’s. Dixon brings to life one dramatic episode in Janet’s life, when words combine beautifully with cello music to underscore the tragic events. During a terrible storm at sea, a ship was about to be shipwrecked, and Janet jumps into a small rowing boat, battling the waves to save the eight men aboard. Janet, who was already suspected of witchcraft, is condemned. How, her fellow islanders ask, could an ordinary woman, without magical powers, have accomplished such a daring feat? In 1629, Janet Forsyth was sentenced to be tied up and taken to the top of the Clay Loan, where she was tied to a stake, strangled and burned.

Ailsa Dixon concludes the show, telling audience members to be brave and continue to speak up, even if they might not be believed.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Margaret Rose.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

![12th Sep: Beauty and the Bester (2025), Limited Series [TV-MA] (6/10)](https://occ-0-8167-92.1.nflxso.net/dnm/api/v6/Qs00mKCpRvrkl3HZAN5KwEL1kpE/AAAABXg-hqm2nG9UDtdiGIWg2b50wdO8tq_tymlm-H2dCLT27nsFw8sa_JK-NGJWZf1VID_-1y9zpSku1wadGYk3EKp5TfCRhrgFadfZNf5iO0VOGND9ceQI618QA09Gad-vleVxZMcStR_yL7V81NAdSaupt4QFRlXg2sx31gYTOLWnRChUA8-CnKR8-PtxdlTyjBiKwsB7oA.jpg?r=f78)