Canadian lawn bowler Kelly McKerihen during the Australian Open in the Gold Coast, Australia, in June. Lawn bowling, often called bowls, is a sport of meticulous strategy and pinpoint accuracy.Jason O’Brien/The Globe and Mail

Mastering It is a summer series to introduce you to Canadians who have sought to rise above being simply good at their chosen endeavour – and who, by perfecting their skill, strive to become the best.

Kelly McKerihen stood on the mat, her eyes focused on a target at the other end of the rink, and calmly and confidently delivered her bowl. The ball rolled toward the small round yellow jack, a few dozen metres away, travelling in an elegant arc, as if tracing a parenthesis. The ball trickled to a stop, nestling itself among a crowd of its red and white peers, finding an opening where it seemed none existed. Most people, given a hundred chances, could not do what she had just done, but for Ms. McKerihen it was just another shot in a lifetime of such moments.

It was June 17, and Ms. McKerihen and her long-time bowling partner Leanne Chinery were facing off against the Malaysian team of Nurul Alyani Jamil and Emma Firyana Saroji in the semi-finals of the Australian Open, arguably the biggest tournament in the small world of lawn bowling. The match started off tight, but now the Canadian pair were ahead 4-1, and it seemed like Ms. McKerihen would soon take control. “Kelly, on these greens, is one of the more prominent forces,” remarked colour commentator Val Febbo, for the benefit of those watching the livestream feed on YouTube, though it was unlikely the viewers at home didn’t know who Ms. McKerihen was.

How this miniaturist made it big with her tiny creations

Meet the master gardener whose plant advice is a road map for life

Lawn bowling – or just bowls – is a sport of meticulous strategy and pinpoint accuracy. The 39-year-old Ms. McKerihen, one of the best players Canada has ever produced, alternately described the game as “chess on grass” and “curling on grass” during an interview a few days before the tournament began on Australia’s Gold Coast. “It’s a very unique sport in the sense that you can play it when you’re five years old,” she said, “and you can play it up until you’re 100 years old.”

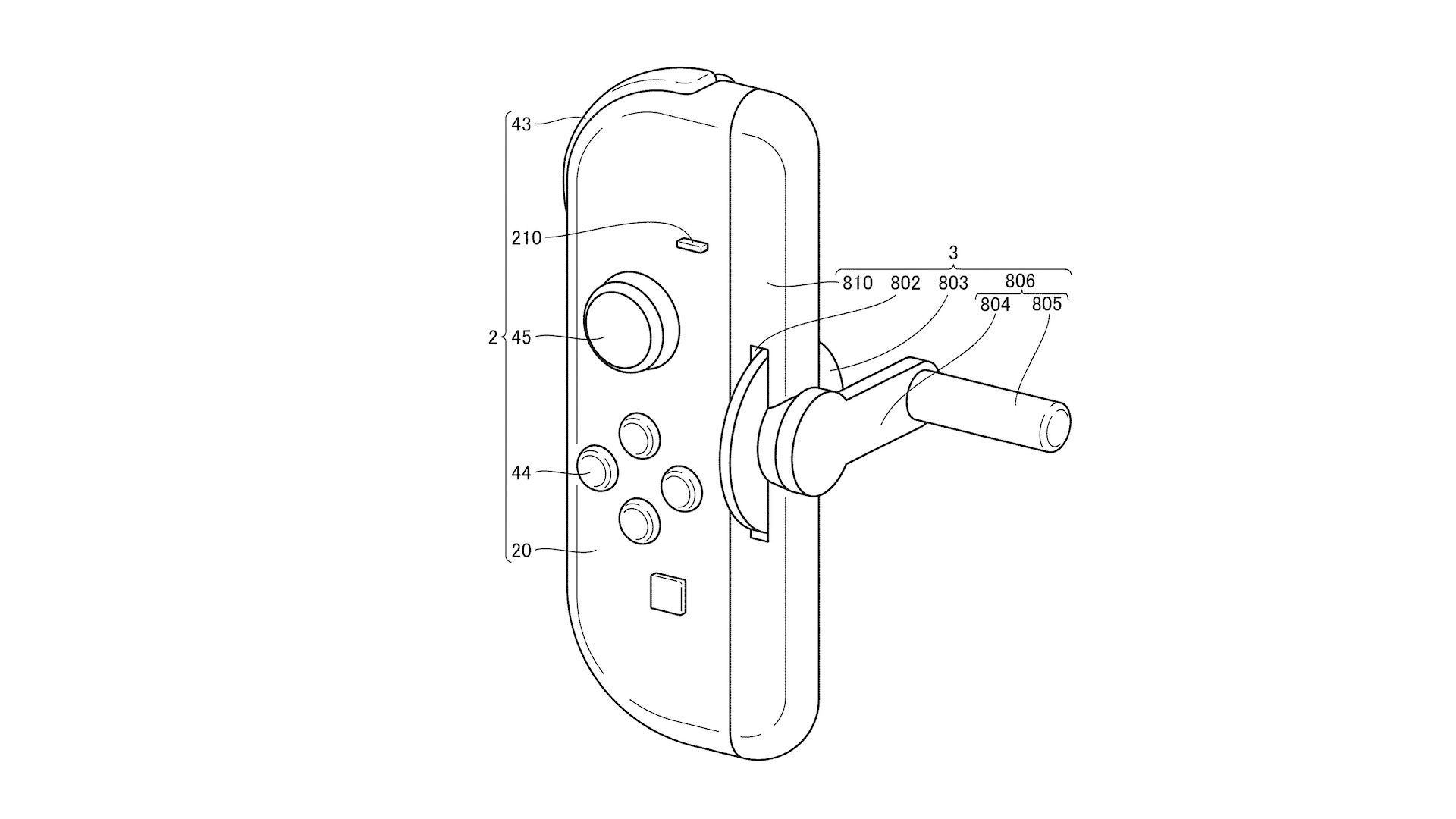

The game is deceptively straightforward. Players take turns tossing balls toward a target, called the jack. The balls are “biased” – meaning they automatically curve as they roll, without players having to add spin – so the skill comes from players deciding where to aim and how much weight to put on each shot. The goal is for at least one of your balls to wind up closer to the jack than one of your opponent’s balls at the conclusion of each cycle of play, called an end.

Lawning bowling balls are ‘biased,’ meaning they automatically curve as they roll.Jason O’Brien/The Globe and Mail

“It sounds cliché, but it’s all about the process,” Ms. McKerihen said. If she’s standing on the mat, looking down the rink, trusting she will make a good shot – something she has done countless times in her playing career – “then hopefully the rest will take care of itself.” As soon as you start worrying about missing, she added, “your process is probably going to suffer.”

“Bowls is such a mental game,” said Ms. Chinery, her teammate, “and mentally she has just become so strong-willed and sharp. She really doesn’t get flustered. When she’s in those high-profile situations, she absorbs that pressure and just responds.”

Last year was a remarkable season for Ms. McKerihen; she skipped a team of four to victory at the Australian Open, part of a stellar run which also included tournament wins in New Zealand and Hong Kong. It all led to her finishing 2024 as the No. 1 ranked female player in the world, an “unreal” accomplishment for a Canadian player, said Ms. Chinery, adding that five years ago, few would have imagined it possible. “Canada is such a minnow country in the sport of bowls.”

Malaysia, on the other hand, is a force. The country captured two medals in the sport at the 2022 Commonwealth Games, versus zero for the Canadians, and will host the inaugural bowling World Cup later this year. And now, in the game against Ms. McKerihen and Ms. Chinery, the Malaysians were mounting a comeback – Canada’s 4-1 lead was melting away. 4-2. 4-3. Then, 5-4 for Malaysia, though the Canadians regained the lead, 6-5, at the halfway point. (Teams play 18 ends.) “A thrilling semi-final we have!” gushed Ms. Febbo.

Ms. McKerihen competes in the Australian Open of bowls in Australia in June.Jason O’Brien/The Globe and Mail

Thrilling and lawn bowling do not usually appear in the same sentence. While its roots date back to ancient Egypt and Greece, in the modern era the sport developed a certain reputation as a pastime of genteel retirees dressed in all white – the uncool cousin of bocce, pétanque and other games that fall under the category of boules. It’s a tired stereotype.

“It’s not an old person’s game,” insisted Ms. McKerihen. “If I got a dollar from everyone that said ‘I wish I took up this sport earlier,’ I’d be quite rich.”

Ms. McKerihen took up the sport as early as imaginable. “She’s been around the bowling greens since she was a toddler,” said her father, Steve McKerihen, himself a decorated Canadian player. While she didn’t start competing until she was about 15 years old, Steve said it was clear from his daughter’s first provincial junior tournament, playing against kids who were three or four years older, that she had a special talent. “We went out with not a lot of expectations,” he recalled. “And she ended up winning.”

It was the first of many. Her résumé includes appearances and medals at top competitions and tournaments, and she’s a nine-time Canadian National Champion. But Ms. McKerihen felt she would never achieve her full potential in Canada, so in 2015, she left for Australia, which she described as “the Mecca of bowls.” Many major tournaments take place in the southern hemisphere, and she wanted to train on greens similar to those she’d be competing on, against the highest calibre of players, year-round. While tournaments in this part of the world offer larger purses than in Canada, lawn bowling isn’t a full-time job, so Ms. McKerihen runs Perfect Trail Coaching in Melbourne, mentoring other players, on the side. She still proudly sports the maple leaf in international competition.

Ms. McKerihen during the Australian Open.Jason O’Brien/The Globe and Mail

Ms. Chinery, another Canadian who lives full-time in Australia, said Ms. McKerihen has invested her whole life in the game. “She immersed herself. She trains hard. She surrounds herself with good players,” she said. “The result of that is what we’re seeing now – her success on the international stage, and being ranked world No. 1.”

Well, she was No. 1 in the world – she’s currently No. 7, one spot up on Malaysia’s Jamil, whose team wound up winning the semi-final match 21-8, knocking Ms. McKerihen and Ms. Chinery from the tournament.

Ms. McKerihen later admitted she was “really disappointed in the moment – quite frustrated and a little bit angry at myself. I could have played a little bit better.” But part of learning to win was learning to lose. “You take a couple of minutes to let the emotion of losing wear off, and look back on it,” she said. “You ask yourself what went really well and what didn’t go so well? And you take the what didn’t go so well piece and [let] that guide your training.”

In a finicky sport like lawn bowling, when the distance between triumph and failure is often measured in millimetres, you might make a perfect shot, but there doesn’t exist such a thing as a perfect game. Mastery is a concept that is always rolling just out of reach.

“As a player, I’m constantly learning and evolving my craft,” Ms. McKerihen said. Even on the days when she feels unbeatable, she knows, deep down, that it’s an illusion. You can be considered the best in the world and still lose on any given day. “So I wouldn’t say that I’m a master. But I think I’m good at what I do.”

As soon as you start worrying about missing, Ms. McKerihen says, ‘your process is probably going to suffer.’Jason O’Brien/The Globe and Mail