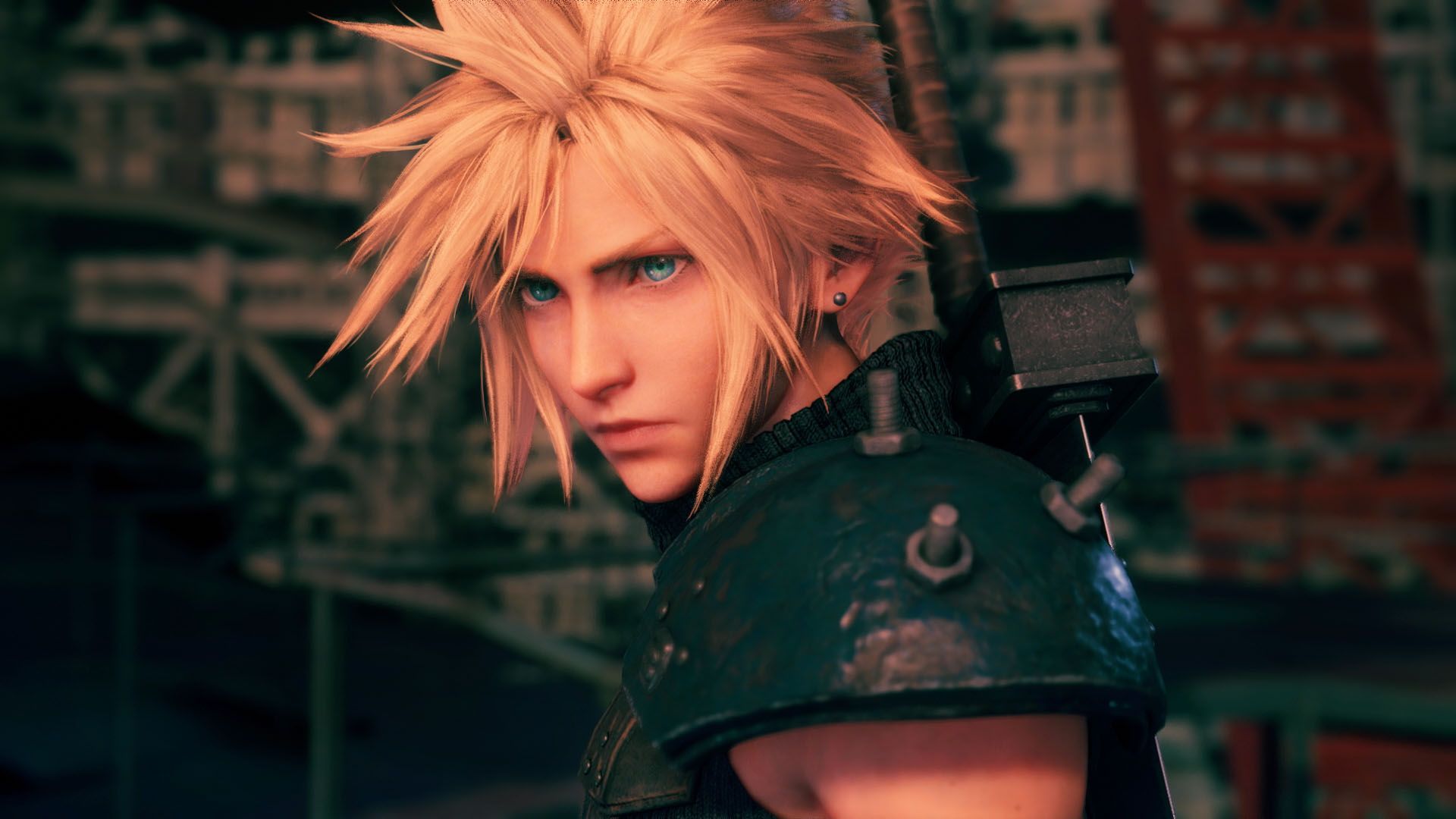

Artist merch has been coveted as a status symbol for decades and it’s become common for musicians to open pop-up merch shops or booths in cities they’re playing.Nick Iwanyshyn/The Globe and Mail

They were all around me. During Morning Glory. During Live Forever. During Wonderwall, when they were on the receiving end of thousands of emotional side hugs and back slaps. Oasis shirts were everywhere at the band’s Monday show at Toronto’s Rogers Stadium: fresh tour shirts, vintage shirts, wildly coveted Adidas-Oasis collaborative jerseys.

I was wearing an Oasis shirt, too. I’d waited 2½ hours in line last Friday to buy it.

This was very uncharacteristic of me. My millennial mind has been conditioned, since I first started going to concerts two decades ago, to keep a lid on such forthright earnestness – to never wear an artist’s shirt to their own concert. To do so would be embarrassing. This concept felt implicit, a question of taste only to be observed and never to be discussed. For years, most everyone else I rubbed shoulders with at shows in bars, arenas and stadiums seemed to abide by this unspoken rule.

Globe and Mail reporter Josh O’Kane with his wife, Kareen at the Oasis concert in Toronto, on Monday.The Globe and Mail

But I’m going to become a dad in a few weeks. There’s so much I want to share with my child. I don’t want to pass down my cynicism. I want my kid to be able to celebrate the things my kid comes to love. With unbridled enthusiasm. Without scoffing. Without baggage.

As Toronto got ready to host the launch of Oasis’s North American reunion tour, I tried to trace the origins of my artist-merch mindset. Discussion threads, think pieces and 20 years of anecdotal observations suggest I’m not alone in this attitude. Of course its most likely genesis is a semi-obscure Gen-X movie: In the 1994 film PCU, Jeremy Piven’s character chastises an inexplicably dreadlocked Jon Favreau. “You’re going to wear the shirt of the band you’re going to go see?” Piven asks condescendingly. “Don’t be that guy.”

Review: A reunited Oasis supernovas a soggy, nostalgic crowd at Toronto’s Rogers Stadium

Why, though? The reason you buy all this merch is to show everyone who passes you in public that you’re a fan. Yet I developed a series of absurd sub-rules about what I wear to shows. To wit: a shirt should fit within the rough genre taxonomy of the artist I am seeing, for instance, or offer a real-ones-know nod – like wearing a Waxahatchee shirt to see MJ Lenderman, the latter of whom provided harmonies on the former’s latest album. Or a wardrobe choice could be approached with a detached irony, like wearing a METZ shirt to Taylor Swift’s 1989 tour.

1/20

These “rules” honestly sound insane now that I have typed them out and read them over. Adhering to them makes for a ridiculously complex way to announce to those around you that you share taste and, perhaps, community.

But community is also the reason that millennials seem to be dropping this attitude. This is augmented, as far as I can tell, by capitalism and Swift.

Artist merch has been coveted as a status symbol for decades. Over the past 10 years or so, it’s become common for musicians to open pop-up merch shops or booths in cities they’re playing outside of the concert venue. Though these have the benefit of providing the artists with side revenue, and of reducing merch lines at shows, they can set off races among fans to snatch up the hottest items. Their popularity surged with Swift’s Eras Tour, with fans sometimes lining up by 7 a.m. on concert days.

Annabella Voaden, of the Cayman Islands, thrifted her band shirt in Kensington Market for $60 a few days before the show, the only Oasis merch they saw after a day of shopping.Nick Iwanyshyn/The Globe and Mail

Of course these fans would wear their merch to the show! The social dynamics shaping pop fandom are far less cynical than those that long governed rock’s once-hegemonic grip on critical sensibility – the fear of selling out, or of being labelled a poseur. That grip once seemed, from the concerts I attended, to extend into hip hop and electronic music, though not mainstream metal. I should have known from watching the joy of Metallica’s merch-wearing megafans at the Rogers Centre in 2017 that it doesn’t need to be hard to be earnestly excited.

We found out my wife, Kareen, was pregnant a few months after we bought Oasis tickets, and a few weeks before Sum 41’s final concert at Toronto’s Scotiabank Arena. I covered that show, and was surprised at the sheer number of gleeful fans wearing concert shirts. As 2025 dragged on, I saw the same thing over and over – even at LCD Soundsystem’s Toronto mini-residency last weekend.

Review: Oasis’s Manchester homecoming gig was like a collective release

Photos from the Oasis’s gigs in Britain and Ireland suggest a sea of gleeful merch wearers; the band’s official Adidas collaborations seemed especially popular, and honestly look pretty sick. So last Friday I decided to scope out the line at the Toronto pop-up shop on Queen Street West. There were 70 people in front of me when I arrived an hour early, and just as many behind me by the time doors opened.

I canvassed a bunch of people in the queue sporting band shirts – some of which had been bought from the shop just the day before. With the exception of a woman who passed by and asked the crowd “What is the Oasis?,” everyone was excited to wear their merch to this week’s shows.

The Adidas collabs were sold out by the time I reached the front, so I picked out a generic, though subtly interesting, tour T-shirt for $60. And on Monday, I made the trek to Toronto’s newest tarmac-straddling stadium to see the lads play.

And I was surrounded. The jerseys I coveted, more bucket hats than I had ever seen in a single place and shirts from the band’s British tour worn by superfans coming back for more. The lights went down, and from our perch near the back, we watched a sea of Oasis logos surge toward the stage. It felt as if we were part of something. I can’t wait for my kid to feel that way someday.