How do forgiveness and reconciliation projects help heal a country’s collective trauma and contribute to its future nation-building? What role does theatre play in this social activity?

These are questions that Kosovo playwright Jeton Neziraj’s new play Under the Shade of a Tree I Sat and Wept, at the Kosovo/North Macedonia International Theatre Showcase 2025, explores. It is deeply collaborative with a team of actors derived from Kosovo, Albania and South Africa, with Greg Homann (AD of Market Theatre, Johannesburg) as its dramaturg and Blerta Neziraj directing. A take on the documentary theatre style, it gathers testimonies from the Truth and Reconciliation Committee post Apartheid in South Africa (TRC) and Kosovo’s Movement for the Reconciliation of Blood Feuds and puts them onstage.

Both events are a few years and more than a thousand miles apart. Post apartheid South Africa’s TRC, which took place in 1995, opted for restorative justice rather than retribution. Led by Bishop Desmond Tutu, it was hoped that the nation could confront and somehow heal from the decades of white persecution and oppression of black people. Kosovo’s blood feuds or Kanun, which took place between Kosovo Albanian families, themselves persecuted in Kosovo, were ingrained into social life. Kanun is where a family must avenge the murder of a male relative via retaliatory killing. More than 4% of the population were confined to their houses in fear for their lives and trapped in these cycles of violence. With a war with the Serbian regime on the horizon and the need for Kosovars to be united to oppose them, folklorist and academic Anton Çetta and other activists set about asking people to forgive such acts, rather than avenge them. May 1st 1990, many forgave at a moving ceremony in Verrat e Llukës.

In South Africa, around 22,000 people testified, and those who had committed crimes were granted amnesty on one condition – that they told the truth and fully disclosed any politically motivated acts.

The TRC promised its citizens freedom, and the Blood Feud Reconciliations worked to encourage Kosovars to find unity against oppression. Yet South Africa is still haunted by severe inequality. The TRC also sacrificed justice for amnesty, raising questions about how forgiveness can survive without it. Kosovo, now an independent country, suffers from corruption. A lack of job opportunities also means that young people often move abroad.

These are the contexts that surround this deeply complex play, which is also a play within a play, a group of scenes which show the actors rehearsing how to stage the testimonies. Homann tells me this was used to create context between these different forgiveness and reconciliation experiments. The device certainly allows exploration into whether and how individual experiences can be reconciled within national peace projects, the price that might be paid for this and provides the framework for creatives to explore artistic responsibility.

The play begins with actors warming up as audience members take their seats and progresses quickly from the warm-up into a courtroom setting.

Jeffrey Benzien, a perpetrator during the apartheid, is asked to show how he tortured his subjects. He sits on top of a female actress and pulls a blue plastic bag over her head, then grabs the back of her feet and yanks the lower half of her body up towards his back. The position is held for more than a few seconds.

The torture could become a motif in the play. Instead, the image is held for longer than it should be held. The audience is being asked to consider what the TRC is giving amnesty for. Here is a terrible act of violence, and it should not be swallowed up into the rest of the play and forgotten – because for the victim, it never can. The TRC did promise that “the truth will set you free.” But who is being set free here? Because if a victim is plagued by trauma which is not relieved by the perpetrator being punished, how can they live through the trauma to forgive – and thus be set free?

Later, there is a scene about a woman called Lethabo whose son was killed by a policeman. As she begins to testify, she is taken ill, and the mic is cut off. In reality, she disappeared in the hospital system and was forgotten by the TRC.

This true story is one of the more hopeless that the production honours. And it is an important one because this is the kind of story that is crying out for artistic treatment. And here, the audience must decide for themselves whether the treatment it gets is justifiable and acceptable (which is why the play within a play is so important). An actor playing the director of the show becomes obsessed with Lethabo’s story and interrupts the actors’ break to relate it to them. As she speaks, she also addresses the audience, so the story becomes performative for them as well. There is something hypnotic about this moment, something energetic, yet also, is the audience not uncomfortable about the director’s interest, which somehow feels unethical?

The actors point out they are on their lunch break and don’t want to listen. But the director can’t help herself. The audience must decide whether the director’s interest is ethical (perhaps the director wishes to restore dignity to victims she believes were being ignored by the TRC). They must also consider whether the actors are inhuman by being indifferent to the suffering they are portraying on stage.

Further on, a scene shows the director visiting Lethabo in the hospital and then devising a scene based on the visit for the play, which bears no resemblance to what took place. The scene at the hospital is also not real. It shows Lethabo unable to answer the director’s question about forgiveness because she is too caught up in haunting visions of her dead son’s hand, cut off at the wrist by his murderer. Two things seem to be happening here – the scene is obviously a manipulation by the creatives and sits outside the meta-play. And it also satisfies the human need for Lethabo’s suffering to be made appropriately specific – we might imagine that she might be in some psychological terror like this.

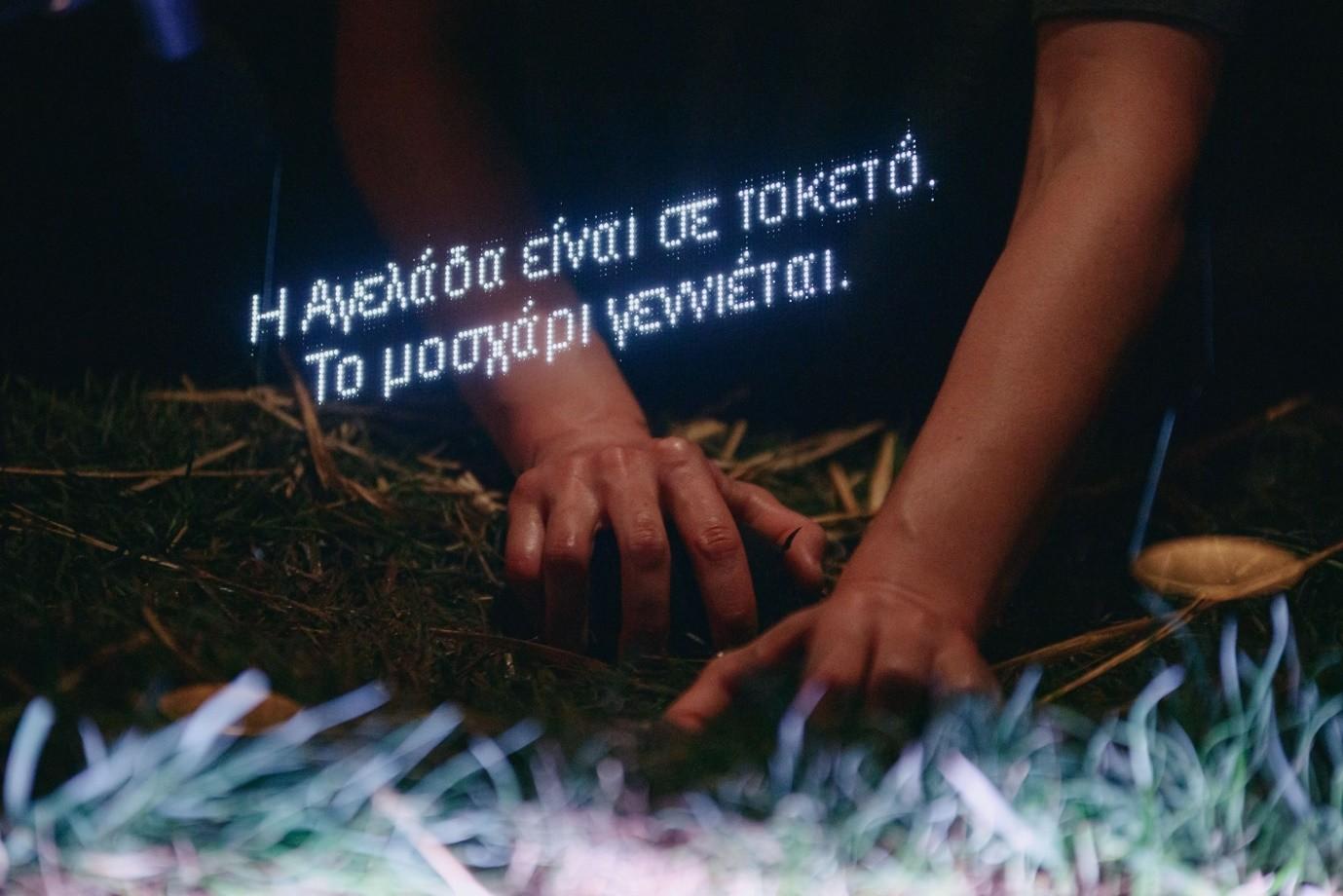

Under the Shade of a Tree I Sat and Wept Photo by Majlinda Hoxha

Yet the scene, which ends up in the play, bears no resemblance to what happened. This helps prompt a discussion between the actors about artistic licence and staying true to the factual events and described trauma.

There is a problem here which the play taken as a whole seems to be asking – and it is also a problem, to a certain extent, which documentary theatre projects must face, and projects like the TRC – and the problem is how to best honour the experiences of victims whose voices are, for whatever reason, cut off and forgotten? Is it best to say that this person’s voice was lost, or to imagine what their experiences might have been (whilst making it clear to audiences that the scenes are imagined)? The show does not give any answers.

Yet a scene about the blood feuds allows the audience to experience the real power of art. At one point, an actor narrates how young males were seen as appropriate targets in the blood feuds once they were taller than a rifle. To demonstrate the absurdity of this, the cast all try to lower their bodies below the upended gun barrel. The image and meaning are profound – that to a mere rifle, which in itself represents a mere ideology, human beings can be held so captive and so bound. When viewed in this way, it seems so ridiculous. The scene is powerful through its startling image – the truth of it is not questioned for this reason (children could be targeted in blood feuds).

The play explores reasons why breaking the hold the Kanuns have is so hard. Not only is there family expectation and generations of it, but the dead also must be vanquished. There is a scene where an actor relates how guilty they feel for choosing not to avenge their father’s death when conscience must surely tell us that it would usually be the other way around. Families are split by the decision to forgive and not seek revenge. No wonder Homann and Blerta Neziraj gather the microphones at the back of the stage in a kind of cage for the confessions and testimonies to be heard in. The “cage” can also seem to form the skeletal branches of a tree – reconciliations in the blood feuds often took place under trees. And in Africa, the tree symbolises different things according to its species. But in South Africa, it symbolises community, justice, life and ancestry.

Towards the very end of the play, Tutu and Çetta meet, though in reality, they never did. And this is turned into a slanging match – at first. The actors get up on chairs and accuse each other of betraying their people – how can there be freedom or forgiveness, which is necessary for that freedom, without victims gaining justice? The two men physically approach each other, scrambling over chairs, which become pathways of hate, until at some point, absurdly struggling over the seats (because doesn’t the image make the struggle look absurd when they could walk over to each other on the floor?), they realise that they should tell their stories. Then they goad each other to go first until they start to do so in unity – “Once upon a time…” as if forming a truce to tell a fairytale.

Blerta Neziraj, who commonly uses physical obstructions to visualise absurd ideologies or philosophies (see A.Y.L.A.N), here has the two shake hands. Only, they can’t stop shaking hands. The handshake, which goes on and on (another stylistic device used by Neziraj to wake the audience up), becomes a scrabbling and pinching at each other. It echoes handshake battles between Trump and Starmer, Trump and Macron, Trump and everyone. Even though they agree to reconcile, people still have to compete and “be better” than the other. And of course, the hand fight reflects back to Lethabo and her nightmarish visions. A hand can do so much – hurt, soothe, haunt.

Tutu and Çetta were trying to do something for their countries and were pioneers of later forgiveness projects. Their bravery should not be underestimated. Should the actors then be more reverential? Yet people always lose sight of the bigger picture because they are constantly struggling in their own lives. Hence, the dinner breaks where the actors show their amused ignorance, where they are not even shocked at it. But then later, in a scene where an actor mops up water spilt by a distressed mother who refuses to let a murderer wash her feet, they are totally absorbed, as if hypnotised, even, in the act of watching it being cleaned up. It is a very uneasy scene, where the actors go beyond being witnesses and almost become voyeurs, or like life-sucking vampires. Is this part of their show? Are they acting? It is not made clear. Around the altar of the spilt blood, many will gather to watch, witness, honour or feed from. These same actors then discuss the ethics of handling testimonies.

For Çetta and Tutu, the forgiveness projects were structural ways to shape their respective countries and help free them from decades of trauma. As the play illustrates, people still suffer. Fortune still seems to favour those who have status.

The play raises many questions for which there are no easy answers. What happens to those people whose experiences are ignored or forgotten in such national projects? How can they cope? Can someone forgive without justice being meted out? Who did the TRC best serve? How do you reconcile an actor’s experience with the ones they are playing on stage when they seem so far apart from each other? What about the audience, who clap and go away, whilst those who were victims still suffer? Can forgiveness take away suffering? And how much can and should you trust the big political actors driving such change, as the TRC or the blood feud reconciliations, how much should you trust the artists who create material from it for you to watch?

At the end of the show, a white blob is raised up towards the ceiling behind Tutu and Çetta as they argue. We don’t see who raises it as it is done mechanically. But then it is lowered, and the actors take hold of it, right it and inflate it. It is a peace dove, perhaps modelled on Picasso’s Peace Dove, the emblem for the first international peace conference in Paris in 1949. Here it is, at first hung up, then rescued, modelled and then allowed to fly – or rather – float. This enduring final image from the show seems to have the last say- we need artists to help us question history and what political actors are trying to do. And it is up to the audience how they make sense of it. This show is about the value of art, then. And it could not come at a more important time.

This post was written by the author in their personal capacity.The opinions expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the view of The Theatre Times, their staff or collaborators.

This post was written by Verity Healey.

The views expressed here belong to the author and do not necessarily reflect our views and opinions.

![The 6 Best Indigenous Cuisine in Toronto [2025] The 6 Best Indigenous Cuisine in Toronto [2025]](https://torontoblogs.ca/wp-content/uploads/2024/12/The-Best-Toronto-39.png)

![2nd Jan: Your Turn to Kill (2019), 20 Episodes [TV-14] (5.55/10) 2nd Jan: Your Turn to Kill (2019), 20 Episodes [TV-14] (5.55/10)](https://occ-0-19-90.1.nflxso.net/dnm/api/v6/Qs00mKCpRvrkl3HZAN5KwEL1kpE/AAAABcswhYWm23P6Kby9UO-kHPX1ZZlTkZ9Ci181x7887pC92mB1UbxzGsLmzNSsPHcZbummwfMMmugcY7MA8heUXZVaDxq-vVcsaBipYYZV7KuO92Bmn1MpcRQQkJMvHbyGhhpLbb96hPz7q5nEcWLvYbgOZlr3K3Roa71BVvLtfa1dmg.jpg?r=f51)