On the first day of rehearsals for Ben Page’s All the Cows Are Dead, the idiosyncratic new musical premiering at Talk Is Free Theatre (TIFT) in Barrie, director Will Dao offered a playful instruction: “Everyone in the room should feel like a detective,” he told the cast and creative team, implying it requires focused collaboration to solve the mystery of staging a show.

Theatre writers are surely also detectives of sorts, and we often conduct our investigation with relatively little information about the inner workings of a production. I was therefore grateful to have the opportunity to observe the Cows team’s detective work as an embedded critic.

I’m sure most world premiere musicals have interesting rehearsal processes — but it helped my excitement level that this one is a site-specific, existential two-hander from one of Ontario’s most risk-taking companies. There’ll also be countless balloons. We’ll get to that.

As detailed in previous Intermission pieces by Aisling Murphy and Luke Brown, embedded criticism is an established but still-uncommon mode of critical writing which trades evaluation for behind-the-scenes reporting and thoughtful analysis of artistic process. The hope is to unearth types of creativity usually invisible to critics and readers.

Aisling and Luke deviated from the journalistic standard of referring to subjects by their last names, with the reasoning that embedded criticism embraces proximity. I’ll do the same, partly because I have an existing relationship with Will; we’re close enough friends that I don’t usually feel comfortable reviewing his work, though I love viewing it and discussing it. Ben and I also both appeared in the massive ensemble cast of a 2022 Toronto Fringe Festival play co-directed by Will — so this was not my first time seeing either artist in-process.

But it was TIFT’s artistic producer Arkady Spivak who opened the conversation that led to this embedding project, and TIFT further supported it by financially compensating Intermission and adding me to the production team’s email list for updates including daily rehearsal schedules.

Ahead of this first entry in a pair of articles, I attended four rehearsals and conducted separate interviews with Ben and Will. I present my rehearsal reflections in chronological order because I found it striking how much the investigation seemed to evolve from day to day; it was a mutable, fleet-footed beast.

Laying the groundwork

Day one took the familiar form of a meet-and-greet followed by a read-through and presentations from members of the creative team. This helped familiarize everyone with the production’s intentions and conceptual framework.

The one-act show follows Anton (Mike Nadajewski), an artisan butcher, as he tutors his nephew Louis (Taylor Garwood) in his profession. Anton pushes around the submissive young poet, who’s not a natural butcher, but possesses a disarming emotional vulnerability. Years pass and the duo’s relationship only grows more unsettled and intense. Ben’s score takes inspiration from Sondheim musicals — not least Sweeney Todd (which TIFT has staged), with its similarly unconventional and meat-cleaving narrative.

After a couple of ice-breakers, Will warned that “I’m going to do a bit of a speech now,” and then, with perfect comedic timing, froze. Because, for family-related reasons, Will is outside of Toronto and directing over Zoom. With associate director Griffin Hewitt there in person and Will on a rolling cart, it’s a factor that has felt surprisingly unobtrusive, especially when the actors weren’t yet on their feet.

The internet soon regulated itself, and Will detailed the production’s concept, explaining that he hoped to emphasize the material’s engagement with “existential dread” by leaning into its Beckett-esque quality.

Set, costume, and prop designer Alessia Urbani expanded on the plan for the visual world: the venue is a slightly claustrophobic room in an office building, and to conjure a sense of liminality, 1910s-1950s garb will clash with set design drawing on postmodern art installation.

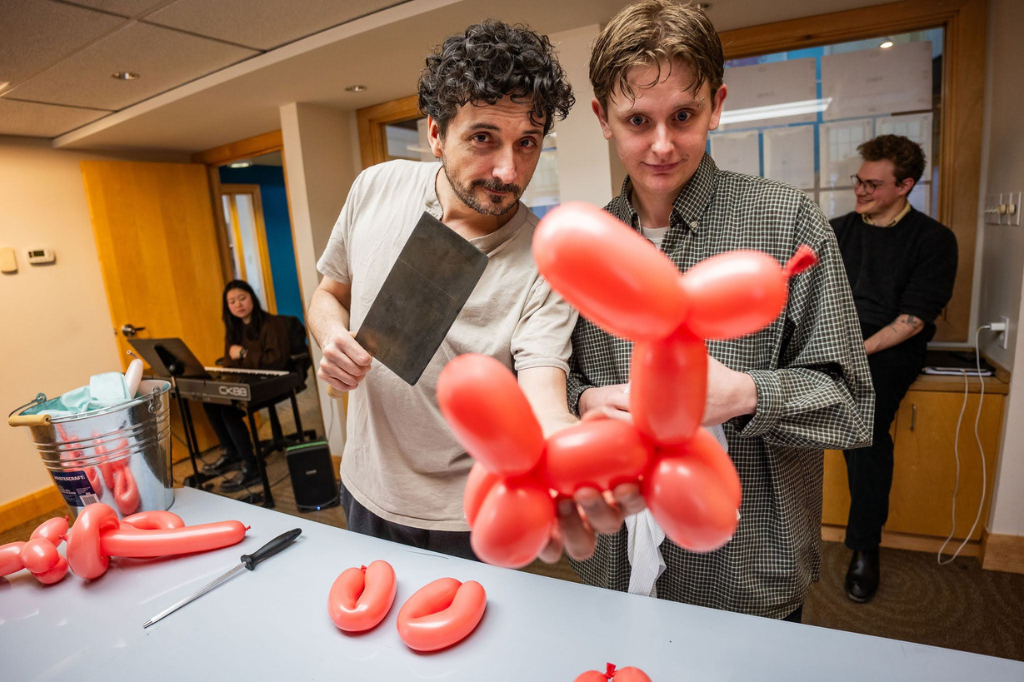

As for the meat the characters slice, shave, and sell? Balloons. A whole lot of ‘em. In sundry shapes and sizes. (The production’s knives are dull, and the butchery non-literal, with each type of meat reacting differently when cut.)

Mike and Taylor read out the script as music director Athena So and Ben collaborated to perform the songs. This was my first encounter with the material, and what left the strongest impression was how fully Ben’s music serviced the story. It seemed to me that almost every phrase, chord, and lyric has a reason to exist; there are no high notes just for the sake of it. Though a world premiere, Cows’ compact structure and thought-through dramaturgy felt ready for the detectives’ scrutiny.

5-6-7-meat

Perhaps because they were performing an upbeat song, artistic impulses poured out of the actors on the first day of staging rehearsals; 105 minutes whizzed by.

During this early number, “I Am a Butcher,” Anton addresses the audience and welcomes them into his shop, gleefully doling out brassy baritone razzle-dazzle to the crowd (arranged along three sides of a narrow room). At the song’s start, Louis scrubs the floor and tries to stay out of the way, before eventually joining in on the fun.

Griffin took the lead on the number’s staging, and references to other musicals proliferated. He told Mike to channel Bob Fosse, so the actor pumped himself up by muttering “Liza, Liza, Liza” before offering jazzy twists on movements like sharpening a cleaver, or cutting a slice of balloon prosciutto and handing it to an audience member (me, in this case).

Taylor moved more lyrically; Griffin described it as “full sadboi poet mode,” with Will invoking Pina Bausch as a reference. But the character is a little clumsy and still learning how to clean the shop, so as he gets up from under the production’s multipurpose set piece — a stainless steel table on wheels — he does a slapstick-y fall that begins with him hoisting a bucket of rags above his head, which Griffin lightheartedly compared to the iconic lifting of Simba in “The Circle of Life.”

If all this Broadway-esque movement vocabulary sounds out of place in a show about existential dread, that may partially be the point. On day one, Will half-jokingly called the musical “a show that wishes it was a musical,” since the characters often seem to be singing as a way of escaping their bleak surroundings. They become showmen to forget the pain.

“We created a scene today”

About a week later, the team tackled a climactic scene that had caused Ben headaches — because, they told the group, it’s where “all the symbols coalesce.”

But together, in a whirlwind of collaboration, the artists deduced a solution.

The scene depicts a charged conflict between Anton and Louis that ignites after Anton mangles cutting a piece of veal. Before rehearsal, Taylor had spoken to Ben about missing a few recently removed lines that allowed Louis to stand up for himself. So the session began with a comparison of various drafts, to find out if different versions could be combined; in the end, Ben only reinstated a couple of lines, and the team resolved to explore Louis’ confrontationality on their feet.

The question: Could a stage direction suggesting that Anton “lunges at Louis and shoves him to the ground” instead become a moment where Anton winds up a slap, but Louis reacts defiantly, catching Anton off guard? After a few minutes of the directors and actors fiddling with different physical configurations for the lead-up to Anton’s aborted slap, Mike found the dramatic option of loudly leaping over the table.

Then they worked through the beat where Louis resists. Since just standing proud didn’t seem definite enough, the solution eventually arose that Louis should lie himself on the table, in the same place where Anton had just been cutting veal. This already-symbolic image grew more heightened with the spontaneous addition of text for Louis — “kill me! kill me!” — then catapulted into an operatic register when Ben and Athena added music under it as Taylor ad libbed a portamento-laced vocal melody.

Finally, the artists considered how Anton should react. Mike tried versions where he picked up his abandoned cleaver before walking away — highly tense, given Louis’ exclamation — but the team ultimately decided Anton is sensitive enough to not even touch a weapon after hearing those words.

The scene work continued onward, but the electricity of that “kill me!” detective work continued to invigorate the room.

“We created a scene today, in many ways,” a beaming Griffin told the group.

A run-through’s magic tricks

As much as theatre unfolds on a moment-to-moment level, character and theme alchemize when scenes play out one after the other. For both artist and critic, the investigation starts to resemble a cross-examination: What does it mean for a character to do this, then that, then this? What ideas, by way of repetition or sheer memorability, escape the confines of an individual scene and reverberate across the entire show?

At the first Cows run-through (“stumble-through,” per industry jargon), delays led to the team halting rehearsal two scenes before the musical’s end. But the alchemy was already underway.

One idea that came to the forefront, for me, was the notion of butchery (and its performance) as a kind of magic. This begins, subtly, with the playful backstory of Louis’ abandonment: “According to the neighbours, [my mother] fell in love with a magician while I was away. Joined the vaudeville.” In a climactic song where Anton sings about the pleasures of butchering, it appears that maybe Louis, too, has ended up living with a magician: “This is the way it should feel,” Anton rhapsodizes. “It’s just like cutting up steak or veal / There’s something inside that’s like magic… / It’s like magic!”

The balloons deepen this parallel, with every cut, every transformation, feeling like a magic trick — from the ribeyes that float away after Anton slices them, to the chain of sausages that serves as Louis’ partner during a tender soft-shoe dance break. There’s real whimsy in all this, but for Anton, meat represents something deeper. “A cow knows that the meaning in its life comes after: when it comes here,” he says.

Butchery is Anton’s magic because it gives the carcasses purpose. But is this enough to also give Anton purpose? When he’s working or singing, it’s possible to believe the claims he makes in the opening scene: “I am happy! I am happy,” he tells Louis, before handing him a knife. “You want to be happy? To live a life with meaning? Hold this.”

But in moments like the one where Anton insists the apprentice has “never loved,” Mike’s voice quavered, hinting at an underlying sadness. I started to feel that if we ever heard Anton soliloquize, the results would be unbearably emotional. He needs a target constantly near him, to instruct, berate, or carve.

“Is it my own misery that makes me miserable?”

During an interview after the stumble-through, I brought my queries about Anton to Ben, and they explained some of the reasoning behind never showing the character alone.

“The big question in the show is: ‘Is Anton happy?’ And if he’s alone with us, then we get an answer,” they said. “I think part of why I like Anton so much is [that] he’s the role model in the show, and he has power to grant… certainty or validation, because he’s so good at what he does. And if we were ever to be alone with him… he wouldn’t be able to give us that anymore. We would see inside of him too much.”

Although musicals often relish in exactly this sort of “too much”-ness — by exposing feelings that would in real life remain hidden — I think Ben is implying it’s richer for the audience to receive clues about Anton’s interior life, but never be fully sure. Perhaps this choice also connects back to Ben’s affinity for aligning song and character: in the dramaturgy of Cows, solos stem from vulnerability, and if a character is as closed-off as Anton, they simply can’t have one.

Louis’ solos certainly demonstrate an immense capacity for emotional openness. One line from the character’s ballad “Handsome” stuck with me because it seems to sum up so many of the show’s reflections on purpose: “If I was special, I’d surely know by now.”

Ben confirmed the thematic centrality of this solo, sharing that it was the first thing written for the project. “It’s maybe the most important song for myself that I’ve ever written,” they said. “I wrote the first two verses in a week, maybe less, and I spent two-and-a-half months trying to write the rest of the song.” According to Ben, Taylor loved the in-progress version, and the two artists began having long conversations about the show and song. “We had a phone call where one of us said… ‘Is it my own misery that makes me miserable?’” recalled Ben. “And I was like ‘OK, I’m gonna call you back. I gotta go.’ And then I wrote the bridge. It starts with [that phrase].”

The nearness of “Handsome” to Ben’s heart comes through in the current draft — and I’m pretty sure Will would say that’s a good thing. When I asked him more about his model of artists-as-detectives, he framed playwrights’ insights as key to an investigation. “Anything Ben says, I really use almost as Bible,” he reflected.

This focus on the material, and Ben’s account of it, gives structure to the process, allowing everyone to contribute without straying far from the available evidence.

“Sometimes what can happen in a room that’s maybe too collaborative is that everyone just wants to do what they want to do, but there’s nothing to be held accountable towards,” says Will. “So when it’s framed as [an investigation], what we’re held accountable towards is the story, or what the story hopes to be in the future.

“How I understand making any project… [is that] in my spiritual brain, the thing that we want already exists somewhere in an abstracted, woo-ey kind of space. And it’s about getting us closer to that.”

‘Til next time

With a process as collaborative as this, it feels right to keep extending the conversation outward. So, for the second and final part of this series, I’ll be bringing another critic into the mix.

We’ll both see Cows, then debrief to compare reactions. Since she won’t have observed rehearsals, the question will then be: How does knowing what happened behind the scenes change your perceptions of a production? (I’ll tell her not to read this piece.)

And in the meantime, if you’re near Barrie, perhaps you could check out Cows and share your take in the comments or over email? I’ve already had so many interesting conversations about the show, and I don’t want to stop.

All the Cows Are Dead runs at 80 Bradford Street in Barrie from January 22 to January 31. More information is available here.