As far as the soundscape was concerned, when I work on other people’s films, that’s primarily what I do: sound. If the industry had been kinder, and more open or diverse when I got out of UCLA film school, I probably would’ve worked in sound, but there weren’t very many avenues for me to work in sound as a professional in the late ’80s. I still really loved sound, so I wanted to spend a lot of time with it. When we were doing the sound, it was basically three months of just working on that. I would work from 6am to 2am. Sometimes, I would sleep on a couch just to get the work done. It was important to build a world. Sound is world-building. I couldn’t actually shoot or make a set look like 1910s Chicago, but I could make the sounds that I would’ve imagined or we would’ve imagined existed. That was a way to get people into the film.

The second thing is that, unfortunately, many of us who are hearing are knuckleheads, and we think that the Deaf don’t have any perception of sound, and they live in a silent world, and that is not true. Deaf people have various perceptions of sound. It’s just not the same as what we have. So with the soundscape, I would talk to Michelle or Chris, and I would ask them about how they were perceiving sound, and a lot of it for Michelle was vibrational. I wanted to make sure that with the sound, we could also push the limits of the frequency so that it would be very low and rumble, and you could feel it. Chris, at that time, was wearing a hearing aid that seemed like it was more attuned to higher frequencies. When he’s performing his dance, I let the hearing aid sound actually stay in. Then, when Nico gets the letter about Malaika, we used high-end sounds from the L train station. So those would also reverberate and get on your nerves, just like nails on a chalkboard.

Those were things that we did. There happened to be a tub in the sound studio, so we put the microphone in a condom and swished it around to try to get some different effects that are in there now. You can hear them now because of the Blu-ray or the “rejuvenated” version of it. Whereas when the film was released, it was on 16mm, and 16mm is mono. We recorded in stereo, and we want people to feel and hear all that stuff.

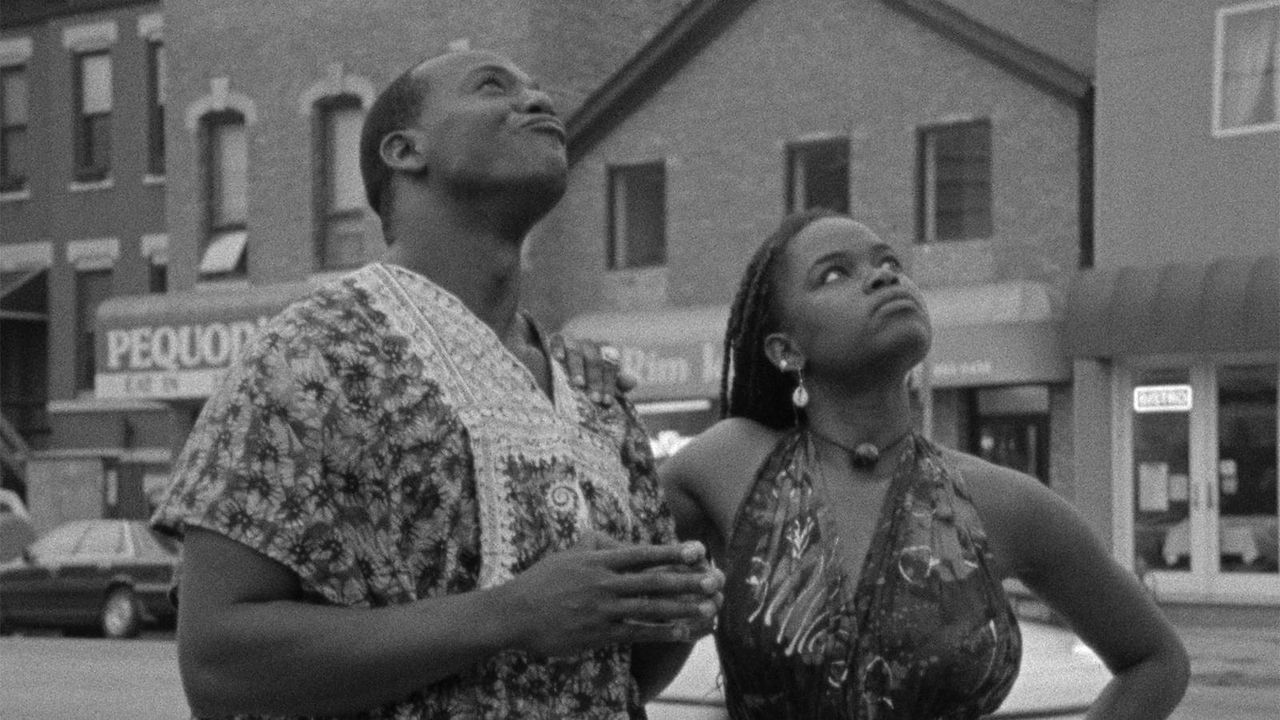

An under-discussed aspect of your work is how sensual it is. It’s certainly present in A Powerful Thang, but even here, you linger so specifically on moments of touch and love. I mean, the film came to you as an act of love. How did you think about lacing these moments into such a tragic story?

We actually just celebrated our 29th anniversary the other day.

Wow, congratulations.

Thank you. He’s pretending that there might be something, another gift, coming.

Compensation II!

We’ll see. [Laughs] But no, you’re right. Cinema is very good at stimulating different senses. You don’t have to have sex on screen for it to be sensual. There’s something very sensual about seeing them just hold each other’s hands in the past when she’s adjusting his hand while learning sign language. Then, when they’re in the contemporary section and they’re making out or just tenderly holding each other after, they’re not going to take the relationship further physically. Those are the moments I’m trying to explore as a director. What do they mean, and how do they push the audience? I do not think audiences are stupid; I think that they bring different things to the work. Why not try to push as much as you can, when you can, in a particular scene? Sensuality is something we still haven’t totally pushed to its limits yet with cinema, I don’t think.

This past year, I’ve spoken to many true American independent filmmakers who are either debuting their first feature or are still relatively early in their careers. You’ve been at this for a long, long time. So, I want to ask you what I’ve asked them: where do you find the perseverance to keep at it, especially in an environment that feels so unfriendly to independent cinema?

Thank you for recognizing me as a, as you say, true independent filmmaker. I like to call myself an “alternative independent filmmaker.” I think that you persevere because you have to. I’m one of those people: I cannot stop making films. It’s in my blood. My dad was an amateur street photographer, always taking pictures of folks in the community. He’s the guy you called when you had a birthday party. There’s something about giving back those images of your community to your community. It is not payment; it sure ain’t payment. I’ve got fame, but I ain’t got a fortune. [Laughs]

It has to be for a higher purpose, or for something bigger than money. It has to be for being able to create communities. I’m following in the footsteps of the LA Rebellion filmmakers. I am an LA Rebellion filmmaker. One of the things that was very clear from working with other LA Rebellion filmmakers is that you involved the community in whatever way you could to be a part of the filmmaking process. That was not lost on me. You had Kathleen Collins, who’s actually from New York, but we still talk about her. She was using her students at City College to make films, and Charles Burnett was driving down Vermont Boulevard or Slauson Boulevard, picking up kids from the neighborhood to come and help do sound, or different things that were involved in the making of the films. To make filmmaking accessible to the community so that you’re responsible to the community—those are the things that keep me going.

That’s what happened with Compensation. There’s a short that’s on the Blu-Ray, Pandemic Bread, which is my last narrative work; we involved whoever was around in the community to be a part of it. In my case, it was students from UCSD, where I teach now, but it was also students in high school, my daughter’s friends, or the kids who hang out at the Malcolm X Library, bringing them into the filmmaking process while we were doing it. That’s important to me. Filmmaking is another way of community organizing or getting people together, and it teaches people about the importance of the arts.

You’ve referred to this restoration as a ‘rejuvenation.’ I’m not going to ask you to define that because you’ve done that in many other interviews. Instead, I want to know what’s rejuvenated you during this whole process?

Well, let me give you a scoop. One of the ways that it’s interesting is that Compensation now has this new life and is going out in the world. One of the things that we’re also working on now is a soundtrack album, which’ll probably be vinyl. One side will have the music score. But on the flip side, we want to try, if we can get enough funding, to do some version of the musical score that would be accessible for the Deaf and hard of hearing. We’ll do some more experimentation with that. We’re really excited, and hopeful that we can get to that soon. A film is a living thing, and it keeps on going, and new audiences or different audiences keep rolling with it. I’m really grateful that that can happen.

As far as what’s rejuvenating me, is actually having these new possibilities. I also want to say something to other filmmakers: a lot of filmmakers, or people on who want to make things, have to be even more creative than we may have previously been because funding sources are drying up more and more. Particularly, the biggest loss to my community is the loss of funding for public television. We can’t stop telling stories. Can’t stop, won’t stop, but we’ve got to figure out other ways of doing things. We have to go back and maybe look at what we’re able to do, even if it’s just taking a photograph a day.

In my case, I’m thinking about doing something else with the photos from Compensation and making a new piece with that. Since I already have it, I don’t have to pay any more money for it. It already exists. So, how can we push our creativity even further? Maybe it involves being in more collectives where we actually do work together. I don’t know. But those are the things that keep me rejuvenated. Certainly, the things that rejuvenate me are being able to work with multi-generational filmmakers and keep on doing great work and things together.